A new enterprise integration pattern has been added to Apache Camel (2.21.0): the “Saga” pattern. This article will show you why, when and how to use it in order to build robust and consistent applications in the cloud.

What is a Saga?

Although the name “Saga” has been widely misused recently, especially in the field of front-end development, in the context of distributed systems the term “Saga” always refers to a pattern for coordinating actions in remote services in order to obtain a consistent outcome. Achieving consistency is something really useful in practice but also difficult, especially in microservice architectures that tend to split the processing logic into multiple autonomous services, usually communicating over HTTP.

What do you mean by “Consistency”?

There’s not a unique definition of the term “consistency”, but here I refer to the widely accepted notion of “keeping the system as a whole in a valid state” (and by “valid” I mean: “respecting all business invariants”).

Let’s try to make it more concrete with an example. Suppose you have designed a system for a travel agency that allows you to buy a trip from A to B, using two external (or internal) services to buy tickets for train (service 1) or plane (service 2).

From a business perspective, your main invariant here is simply stated:

For any trip from A to B, the agency should buy tickets for all sub-routes (train or flight) that take the customer from A to B, or none of them

It means, in simple words, that when a user asks to go from London to Florence, the agency should buy a flight from London to Rome and a train from Rome to Florence. But it should never buy a train from Rome to Florence if the flight from London to Rome is full (or too expensive). We should buy the full trip or tell the user that the trip cannot be reserved.

But the problem is that we have two distinct systems for buying train tickets and reserving flights. How do we coordinate them?

Now, use your imagination, this is a very common problem and happens in many contexts!

How did people use to solve this problem? (Transactions)

This is a classic problem in distributed systems and the traditional way to solve it is… with transactions, of course!

I’ve been a consultant for many years and I can tell you that the most common architecture used by people is the big monolith with a gigantic relational database where multiple application modules store data (and sometimes also communicate by writing and reading data from the DB).

So if that is your architecture, the problem is simply solved by wrapping the calls to the flight module and the train module inside a transaction, so that if one of the two calls fails, the whole transaction is rolled back and your system preserves the invariant (transactions are indeed ACID, where the C means “consistency”).

And what if the system is distributed? Well, there are distributed transactions. One of the most widely used specification for distributed transaction is XA and it allows applications and resources to execute actions in the context of a globally defined transaction that preserve the ACID properties. So you can have a ACID transaction that can span multiple databases or even multiple distributed services (the transactional context can be propagated across services).

So, why don’t we just use distributed transactions?

There are many drawbacks to using distributed transactions.

The most evident one is that protocols and specifications for propagating a transaction context between two remote services are missing or under-developed when we want to connect services developed using different languages. Java is probably the language that has the best support for local and distributed transactions, but many other languages completely lack support for the most basic features.

But also in Java, if you use a NoSQL database instead of a good old RDBMS, chances that you can use (ACID) transactions are pretty low.

And what if you want to use an asynchronous toolkit like Rx-Java on Vert.x or Project Reactor on Spring-Boot 2? Now chances that you can use transactions are close to zero (although there’s some work going on…).

But there are other reasons why one would avoid using distributed transactions in the context of microservice architectures or distributed systems in general. One reason is that a transaction often causes locks to be created on resources and when you have something unreliable between parts of your system, like the network, it may be the case that the locks are kept for a time longer than expected, creating also issues to other parts of the application.

This problem becomes more important when the two services that want to participate in a transaction belong to two distinct organizations. If you ask an architect to connect two services in a way that a problem in one service may also propagate to the other, that architect would probably think twice before doing such choice (or better three times). And distributed transactions are a kind of heavyweight link between services that one would like to avoid. A service running slowly increases the duration of global transactions also in the other services. A failure of one service may leave locks in the database of another service for too long.

In summary, if you want to use distributed transactions, you also need to trust the other side..

That’s probably the main reason why people prefer to keep the boundaries of distributed transactions very narrow (and make use of distributed transactions only when necessary).

And now we have Sagas

You may have heard of sagas in a talk about domain-driven design (DDD) or event-sourcing. In fact sagas are a central part of both approaches. But a saga is not necessarily linked to that context, it’s a generic pattern that can be used to coordinate remote services.

In fact, since version 2.21.0 of Apache Camel, it has become a enterprise integration pattern (EIP).

A Saga can be defined as:

A series of actions that belong to a business activity that should be all executed correctly by (remote) participants or otherwise compensated

Sagas fit more naturally into the way the natural world works (at least, our understanding of it). Let’s take the previous example of the travel agency and suppose a user wants to reserve a trip that includes buying a train ticket and a flight.

- A system developed with transactions would try to reserve both the flight and the train ticket at the same time. If it doesn’t succeed, none of them will be booked.

- A system using the saga pattern will try to reserve the train and the flight independently. In case of failure in one of the two reservations, the other one will be canceled.

For this reason, a saga does exactly what a human would do in this scenario: check if the full trip can be reserved, try to book, then cancel in the event of issues.

On the other side:

There is no such thing as a transaction in the real world

Yes, ask Walter White if you don’t believe me…

Sagas in Apache Camel

Designing a saga is fairly easy in Apache Camel. Let’s see an example.

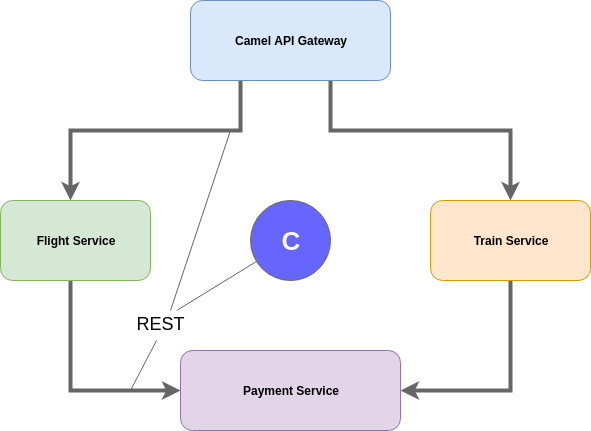

I’ve designed a sample quickstart system with the following (microservice) architecture.

The full example is available here: https://github.com/nicolaferraro/camel-saga-quickstart.

You can see the following services:

- API Gateway: a sample camel app that is the main entry point (and will continuously start sagas simulating real users)

- Flight Service: a service that sells flights

- Train Service: a service that sells train tickets

- Payment Service: a service that allows both services to request payments

- The big “C” in the middle is a LRA Coordinator (see below!)

The basic workflow is:

- The saga starts

- The gateway will reserve a flight (include payment)

- The gateway will buy a train ticket (include payment)

- Saga is completed (or compensated in case of issues)

But since I am evil, I’ve made the payment service to fail with 15% probability. This means that e.g. if the payment service fails during the flight reservation process, we should cancel the reservation. But in any case (succeeded or not), we should also cancel the train reservation if it has happened in the meantime.

It sounds complex to maintain all services (train, flight and payment) in a consistent state, but I’ll show you it’s fairly easy with the Saga EIP in Apache Camel.

So, show me the code!

Camel API gateway

Writing the main gateway route is straightforward:

from("timer:clock?period=5s") // <-- replace it with rest() definition to create a real gateway

.saga() // <-- start a new saga

.setHeader("id", header(Exchange.TIMER_COUNTER))

.setHeader(Exchange.HTTP_METHOD, constant("POST"))

.log("Executing saga #${header.id}")

.to("http4://camel-saga-train-service:8080/api/train/buy/seat") // <-- action 1

.to("http4://camel-saga-flight-service:8080/api/flight/buy"); // <-- action 2

// you can also .multicast() the two calls

And this completes the saga definition.

Ok, we need also to write the services, but writing them is also easy.

Camel Saga-aware Service

Let’s take the train service as an example. A Camel saga-aware service can be implemented like this:

rest().post("/train/buy/seat")

.param().type(RestParamType.header).name("id").required(true).endParam() // <- from caller

.route()

.saga() // <-- join the saga with "supports" propagation

.propagation(SagaPropagation.SUPPORTS)

.option("id", header("id"))

.compensation("direct:cancelPurchase") // <-- the compensation endpoint

.log("Buying train seat #${header.id}")

.to("http4://camel-saga-payment-service:8080/api/pay?bridgeEndpoint=true&type=train") // <-- propagate saga to payment service

.log("Payment for train #${header.id} done");

from("direct:cancelPurchase") // <-- The compensation route

.log("Train purchase #${header.id} has been cancelled");

And that’s it.

The compensation endpoint is just the endpoint that must be called in order to cancel a reservation. It’s declared in the main route and invoked by Camel when it’s necessary to compensate (Camel detects failures in any point of the Saga and reacts accordingly).

Look at the Camel Saga EIP documentation. There are many other options and features you can use. E.g.

- Adding timeouts for saga completion

- Receiving saga completion callbacks

- Asynchronous saga execution

Running the example

The example can be run on Openshift. Just install Minishift, connect to it and use the following commands to start everything.

git clone [email protected]:nicolaferraro/camel-saga-quickstart.git

cd camel-saga-quickstart

oc create -f lra-coordinator.yaml

mvn clean fabric8:deploy

It leverages the fabric8 maven plugin.

How do Camel Saga and “Long Running Actions” work

If you arrived here you may be wondering how this saga machinery works under the hood.

Saga is a Camel EIP and can have different implementations. The base implementation keeps all data about the status of every saga in memory, so it’s not fault-tolerant. If the application crashes, everything is lost. Also, propagation across services cannot be used with the base implementation.

But Camel 2.21.0 ships also a new module called camel-lra and a spring-boot starter (camel-lra-starter).

LRA stands for “Long Running Action”, that is the name of a Microprofile specification under-development (see microprofile-lra). Its main implementation is already available and developed by the Narayana team in https://github.com/jbosstm/narayana/tree/master/rts/lra.

I’ve provided Openshift resources to install a basic LRA coordinator in the quickstart example (file lra-coordinator.yaml).

In spring-boot, the camel-lra service can be enabled by adding the camel-lra-starter module to the pom.xml file and the standard Spring-Boot application.yml file:

camel:

service:

lra:

enabled: true

coordinator-url: http://lra-coordinator:8080

local-participant-url: http://my-url-as-seen-by-coordinator:8080/context-path

You need to set the camel.service.lra.enabled=true flag (so it will be the backing implementation of the .saga() EIP) and provide:

- The coordinator base URL

- The participant (this service) base url in order to receive callbacks from the coordinator

Note that these two settings are overridden when running the quickstart inside Openshift.

Yes, in case you’re wondering, the coordinator and the participant services communicate over REST. This allows to easily extend support for LRA to other languages.

A LRA coordinator is a stateful component. Indeed it’s the only stateful piece of the quickstart but you don’t need to

customize it. It’s a generic component that your application will just use through the camel-lra module.

Being stateful and persistent, it adds fault tolerance to your application: your business invariants are eventually respected even in the case of failure.

A Brief Overview of the Protocol

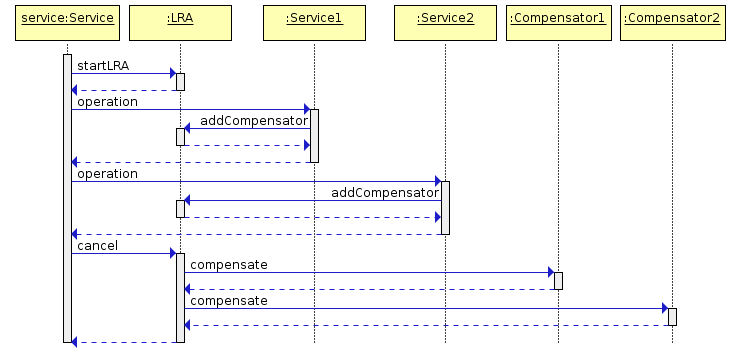

Nothing magic happens under the hood. The protocol is fairly simple and is explained briefly by the following diagram:

Here service is the application starting the saga (the API Gateway in the previous example).

Before doing any operation, it first creates a saga (startLRA operation) by communicating with the coordinator (REST).

Then, it can talk with other services: Service1 and Service2 in the picture.

The Long-Running-Action HTTP header is used to propagate the LRA context to the downstream services.

Before Service1 and Service2 do any operation they join the saga by registering a compensating action (Camel URI) in the coordinator (addCompensator operation, another REST call).

Then, after the main actions are executed, the whole saga can complete normally (everything fine) or exceptionally (like in the diagram). In case of abnormal termination of the saga, the LRA coordinator will ensure that all registered compensating actions are called.

And what if a compensating action fails? Of course, the coordinator will retry again and again. This means that compensating actions must be idempotent and assume they might be called more than once.

Caveats

Idempotency and … “Commutativity”

We have seen that a compensating action must be idempotent, because the LRA coordinator can call it multiple times, especially in case of network error or application unavailability.

But there’s a more severe restriction that you need to respect in order to write correct services: a compensating action should be commutative w.r.t. the main action.

It means that, since we are in a distributed environment, sometimes the compensating action may be called by the LRA coordinator before the main action has completed (or has even started).

So, for example, your train service must be able to cancel a reservation even if such reservation is still not present in the system, and the reservation must be considered already canceled when (and if) it’s created by a late running main action in the future.

Sometimes it can be hard to satisfy the commutativity restriction… but there can be alternative solutions…

A Bit of Q&A

Is the LRA Coordinator a single point of failure?

- Not necessarily, e.g. the Narayana team is working to provide scalability and failover for the coordinator.

Isn’t a Saga just a kind of distributed transaction?

- No, a saga is composed of independent actions that are executed in different services during a long timespan (a transaction completes within few seconds, usually).

- It’s true that in some cases you need to register a completion-callback in the downstream service to finalize the action and this is similar with what happens with 2-phase-commit transactions. But this is not always necessary. E.g. the train service above has not registered any completion endpoint because once a seat is reserved by one customer, it cannot be reserved by another one, and it does not matter if the reservation is confirmed (saga completed) or not (saga in progress).

Resources

Have Fun!